The methods used by the central bank to influence the total volume of credit in the banking system, without any regard for the use to which it is put, are called quantitative or general methods of credit control.

These methods regulate the lending ability of the financial sector of the whole economy and do not discriminate among the various sectors of the economy. The important quantitative methods of credit control are- (a) bank rate, (b) open market operations, and (c) cash-reserve ratio.

2. Qualitative or Selective Methods:

The methods used by the central bank to regulate the flows of credit into particular directions of the economy are called qualitative or selective methods of credit control. Unlike the quantitative methods, which affect the total volume of credit, the qualitative methods affect the types of credit, extended by the commercial banks; they affect the composition rather than the size of credit in the economy.

The important qualitative or selective methods of credit control are; (a) marginal requirements, (b) regulation of consumer credit, (c) control through directives, (d) credit rationing, (e) moral suasion and publicity, and (f) direct action.

The bank rate policy is the traditional method of credit control used by a central bank. The bank rate or the discount rate is the rate at which a central bank is prepared to discount the first class bills of exchange. According to M. Spalding, the bank rate is “the minimum rate charged by the central bank for discounting approved bills of exchange.”

In its capacity as ‘lender of last resort’, the central bank helps the commercial banks by rediscounting the first class bills (i.e., by advancing loans against approved securities). The rate of interest which the central bank charges from the commercial banks for rediscounting the bills is called bank rate.

The bank rate is distinct from the market interest rate. The bank rate is the rate of discount of the central bank, while the market interest rate is the lending rate charged in the money market by the ordinary financial institutions.

There is a direct relationship between the bank rate and the market interest rates. A change in the bank rate leads to change in other interest rates prevailing in the market. In this sense, bank rate is the effective rate for lending or borrowing which prevails in the market.

Bank rate policy aims at influencing- (a) the cost and availability of credit to the commercial banks, (b) interest rates and money supply in the economy, and (c) the level of economic activity of the economy. A rise in the bank rate makes the credit costlier, reduces the volume of credit, discourages economic activity and brings down the price level in the economy.

Similarly, a fall in the bank rate makes the credit cheaper, increases the volume of credit, encourages the businessmen to borrow and invest, and increases the levels of economic activity and the price level.

Various effects of bank rate policy are discussed below:

i. Effect on Cost and Availability of Credit:

Bank rate policy influences both the cost and the availability of credit lo the commercial banks. By changing the bank rate, the central bank affects the cost of credit; by raising the bank rate, it raises the cost of credit and by lowering the bank rate, it lowers the cost of credit.

By changing the eligibility rules or the conditions under which the commercial banks can secure loans the central bank influences the availability of credit; strict eligibility rules make it difficult, and lenient eligibility rates make it easy, for the commercial banks to get loans from the central bank.

The cost of credit (or the price dimension of the bank rate policy) determines the quantity of borrowing demanded from the central bank and the availability of credit (or the quantity dimension of the bank rate policy) determines the quantity supplied by the central bank. When quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied, a zero change in the bank rate policy will be appropriate.

ii. No Simultaneous Determination of Interest Rates and Money Supply:

The central bank, through its bank rate policy, is able to influence the interest rates and the money supply in the economy. Changes in the bank rate influence the interest rates in the money market. Changes in the amount that the central bank is willing to lend influence the money supply. But, the central bank cannot simultaneously set both interest rates as well as the money supply. It must choose one goal or the other.

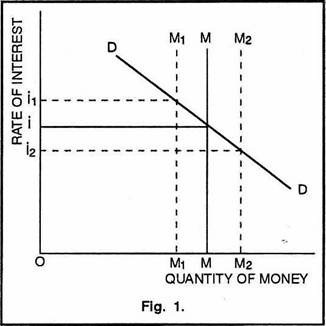

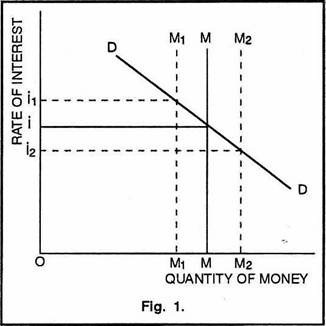

In Figure 1, DD is the community’s demand for money curve. MM is the supply of money curve. Oi is the rate of interest. Given the demand for money curve, DD, if the central bank wants the rate of interest to rise from Oi to Oi1, it must reduce the supply of money from OM to OM1; and if it wants the rate of interest to fall from Oi to Oi2, it must increase the money supply from OM to OM2.

Similarly, if the central bank desires to reduce the money supply from OM to OM1, it must raise the interest rate from Oi to Oi1; and if it desires to increase the money supply from OM to OM2, it must reduce the interest rate from Oi to Oi2. Thus, given the demand for money function, the central bank cannot simultaneously choose an interest rate and the money supply.

iii. Effect on the Level of Economic Activity:

The bank rate policy affects the level and structure of interest rates and thereby the level of economic activity in an economy. A change in the bank rate leads to a corresponding change in the other interest rates of the market. This makes credit either dearer or cheaper. The changes in the market interest rates affect the willingness of the businessmen to borrow and invest. This will, in turn, affect the level of economic activity and the price level.

iv. The Announcement Effect:

The announcement effect of a change in the bank rate influences the credit psychology in the economy. A rise in the bank rate is regarded as the official signal for the beginning of the period of relatively dearer money and a fall in the bank rate is an indication for the onset of a cheaper money phase.

v. Bank Rate Policy during Inflation and Depression:

Bank rate policy is used to control the inflationary as well as deflationary situations in the economy. During inflation, the central bank increases the bank rate. As a result, other interest rates in the money market will rise, thereby rising the cost of bank credit.

This will discourage the businessmen from borrowing from banks. The Volume of credit will decrease, the level of economic activity will decline and the price level will fall.

During depression, the bank rate is reduced. It will reduce the market rates of interest, make the bank credit cheaper, encourage the businessmen to borrow, and invest, push up the level of economic activity and the price level.

vi. Effect on Balance of Payment:

A rise in the bank rate will set right an adverse balance of payment. An adverse balance results in an outflow of gold. As the bank rate is raised, other interest rates in the money market go up.

As a result, there will be a movement of foreign capital into the country because of better returns and stoppage of capital going out of the country. Moreover, the demand for domestic currency will rise, raising its value and making the exchange rate more favourable.

Hawtrey and Keynes have developed different lines of thought regarding the effect of bank rate policy. According to Hawtrey, the bank rate policy alters the short-term interest rates in the market, which influence the level of economic activity in the economy. Keynes, on the other hand, was of the view that the economic activity in the economy is influenced by the effect of the bank rate on the long-term interest rates.

According to Hawtrey, changes in the bank rate result in changes in the short-term interest rates which, in turn, influences the cost of borrowing from the commercial banks and the willingness of the dealers to hold stocks of finished goods through bank loans. This will affect the economic activity in the economy. When the bank rate rises, short-term interest rates rise consequently.

This discourages the traders to hold finished goods because now the cost (i.e., interest burden) of holding such stock has risen. They will curtail their existing stocks of finished goods and also reduce their orders with the industrialists. In view of falling orders, the industrialists will reduce production and employment.

Unemployment of workers will reduce general demand for goods and services, and, thereby their prices. Thus, raising the bank rate, through raising the short-term interest rates, adversely affects the holding of stocks and reduces the business activity in the economy.

According to Keynes, changes in the bank rate cause changes in the short-term as well as long-term rates of interest that influence the economic activity. When the bank rate rises, the commercial banks immediately raise interest rates. As a result, the investors tend to avoid borrowing from the banks and tend to raise funds by selling long-term securities.

The large sales of long-term securities and the resultant diversion from long- term to short-term securities will lower the prices and raise the interest rates of long-term securities. Thus, whenever bank rate rises, the short-term interest rates go up immediately and after a while long-term interest rates also move upward.

As a result of rise in the long-term interest rates, given the marginal efficiency of capital, the businessmen will reduce their investment and the reduction in investment will result in contraction in economic activity, leading to a fall in production, employment and prices.

In fact, the two economists emphasised two different aspects of the same problem. While Hawtrey emphasised the effectiveness of short-term interest rates in influencing the level of economic activity, Keynes emphasised the effects of change in the long- term interest rates on the level of economic activity.

The correct approach would be to integrate the two views to have a complete understanding of the influence of the bank rate policy on the volume of credit and level of economic activity.

The success of the bank rate policy is based on the following assumptions:

(i) The commercial banks possess sufficient quantities of eligible securities.

(ii) Commercial banks are not prejudiced against rediscounting their eligible securities with the central bank.

(iii) Commercial banks keep only minimum cash reserves just sufficient to carry on their day-to-day operations. For additional cash requirements they freely approach the central bank.

(iv) There exists a close relationship between the bank rate and other interest rates.

(v) Borrowing and investment of the businessmen depend upon the prevailing interest rates of the commercial banks. In other words, a rise in the interest rate restricts borrowings and investment, while a fall in the interest rate encourages borrowing and investment.

(vi) There exists an elastic economic structure. In other words, prices, costs, wages, employment, and production are flexible enough to change according to the changes in borrowing and investment by businessmen.

(vii) There exist no artificial restrictions on the international flow of capital.

Limitations of Bank Rate Policy:

As these assumptions are not fully achieved in reality, the bank rate policy suffers from a number of limitations:

i. Insensitivity of Investment:

The Radcliffe Committee in Great Britain and the American Committee on Money and Credit have pointed out that the entrepreneurs are not very sensitive to changes in the interest rates while making their investment decisions. The investment decisions are influenced more by business expectations than by changes in the rate of interest. During boom period, when the businessmen are over- optimistic and the marginal efficiency of capital is high, the demand for bank credit cannot be easy checked by increasing the bank rate.

ii. Ineffective in Controlling Deflation:

Bank rate policy is more ineffective in off-setting depression than in controlling inflation. When bank rate is lowered during a period of deflation, the resulting lower rates of interest may not be able to induce the entrepreneurs to borrow and invest more because of falling prices and falling profits.

iii. Conflicting Effects:

The internal and external effects of the bank rate policy may be conflicting. If, for example, the bank rate is raised to control domestic inflation, the resulting rise in other interest rates may attract short-term foreign funds into the country. This may offset the anti-inflationary effects of the bank rate policy.

iv. Ineffective in Controlling Balance of Payments Disequilibrium:

The success of bank rate policy in correcting the balance of payments disequilibrium presupposes the removal of all artificial restrictions on foreign exchange and on the international flow of capital. But, in reality this condition is nowhere satisfied.

v. Indiscriminatory:

The bank rate policy is indiscriminatory in nature. In other words, it makes no distinction between the productive and unproductive activities in the country. For example, if the bank rate is raised to control speculative activities, it will also adversely affect the genuine productive activities.

vi. Non-Dependence of Commercial Banks:

In modern times, the commercial banks have acquired sufficient liquid resources of their own. As a result, they have become more and more independent and do not feel the necessity to approach the central bank for financial accommodation.

The necessary conditions for the success of bank rate policy are more satisfied in the developed countries than in underdeveloped countries.

In the underdeveloped countries, the bank rate policy has been called into question due to the following reasons:

(i) In the underdeveloped countries, the money market is divided into two sectors- (a) the modern banking sector; and (b) the indigenous banking sector. While the bank rate policy may be effective in the modern banking sector, comprising commercial banks, it has no effect on the indigenous bankers (e.g., sahukars, money lenders, etc) who are not dependent on the central bank for financial accommodation.

(ii) The modern banking sector in the underdeveloped countries lack coordination among its constituent units so that the bank rate policy does not become fully effective.

(iii) Most of the commercial banks in the underdeveloped countries are in the habit of keeping excess cash reserves over and above the minimum requirements. This reduces their dependence on the central bank for financial accommodation.

(iv) In the underdeveloped countries, there is no availability of eligible securities in large quantity to be rediscounted from the centre banks.

(v) The presence of substantial non-monetised sector (i.e., barter transactions) also render bank rate policy ineffective in the underdeveloped countries.

(vi) The, economies of the underdeveloped countries are far from elastic in the sense that wages, costs and prices do not respond readily to changes in the volume of credit.

(vii) The empirical evidence suggests that investment expenditure in the underdeveloped countries is generally interest-inelastic. This is mainly because of the fact that interest cost forms a very low proportion of total cost of investment in these countries.

(viii) In planned developing economies where the public sector accounts for the larger part of the nation’s investment and is equipped with a set of more direct and powerful instruments of controlling the level of economic activity, the bank rate loses much of its importance.

The bank rate policy remained successful during the prevalence of international gold standard. But, after the Great Depression of 1929-33, the importance of the bank rate as a method of credit control declined.

The various factors responsible for the decline of the bank rate policy are given below:

I. Decline in Bills of Exchange:

The bank rate operates through rediscounting of bills of exchange. But, after the World War I, there has been a marked decline in the use of bills of exchange as an instrument of financing trade mainly due to the contraction of international trade and the increasing use of treasury bills or other short-term government securities.

II. Economic Rigidities:

The growing tendency of almost all countries after the World War I towards economic rigidities, such as stabilisation of prices, wages, interests, etc., has reduced the importance of bank rate.

III. Importance of Fiscal Policy:

The cheap money policy followed by most of the governments during and after the Great Depression of 1930 failed to revive economic activities. On the other hand, fiscal policy proved quite effective in offsetting the effects of depression. Thus, the monetary policy receded into the back- ground and the fiscal policy gained more and more importance.

IV. Increased Deposits:

The deposits of commercial banks have also increased due to the inflationary conditions. As a result of their strong financial position, the commercial banks do not approach the central bank for financial accommodation.

V. Other Methods:

In recent years, other and more effective methods of credit control such as open market operations, variable cash reserve ratios, selective credit controls, etc, have been developed. These methods have caused a further decline in the importance of bank rate policy.

VI. Less Sensitive to Changes in Interest Rates:

Recent changes in taxation and production costs have made the businessmen less sensitive to the changes in the rates of interest.

VII. Changing Methods of Business Financing:

Recent changes in the methods of business financing have also reduced the importance of interest rates and hence of the bank rate in investment decisions. The businessmen now resort more to ploughing back of profits and accumulation of surplus funds and less to borrowing from commercial banks for financing their economic activities.

Though the bank rate policy suffers from serious limitations and though it has not proved very effective in both developed and underdeveloped countries. Its importance as a useful weapon of credit control, particularly in fighting inflationary pressures in the economy cannot be underestimated.

To use the words of De Kock, “The discount rate of central bank has nevertheless a useful function to perform in certain circumstances and in conjunction with other measures of control.”

The significance of the bank rate policy is three fold:

(i) The bank rate indicates the rate at which the public can get accommodation against the approved securities from the banks.

(ii) The bank rate indicates the rate at which the commercial banks can get accommodation from the central bank against the government and other approved securities.

(iii) The bank rate reflects the credit situation and economic condition in the country. A rise in the bank rate may be regarded as “the amber coloured light of warning” to the commercial credit and business activities, while a fall in the bank rate may be looked upon as “the green light indicating that the coast is clear and the ship of commerce may proceed on her way with caution.”

“In view of the shortcomings of the bank rate policy, the development of open market operations-the purchase and sale of government securities and other credit instruments in the open market-as an additional and, to some extent, alternative instrument of central bank policy is a logical step.”

Open market operations refer to the deliberate and direct buying and selling of securities in the money market by the central bank.

In the narrow sense, open market operations refer to the purchase and sale by the central bank of government securities in the money market. In the broad sense, open market operations imply the purchase and sale by the central bank of any kind of eligible paper, like, government securities, bills and securities of private concerns, etc.

I. Effects on Reserves of Commercial Banks:

Open market operations bring changes in the reserves of the commercial banks. When the central bank purchases securities, the reserves of the banks increase exactly by the same amount of the purchase. The banks will expand credit multiple times which will ultimately lead to an increase in the level of economic activity. Opposite effects will be obtained when the central bank sells securities.

II. Effect on Interest Rates:

Purchase or sale of securities affects their prices as well as their yields. When the central bank purchases securities aggressively, it increases their prices and thereby lowers their yields. Similarly, an aggressive sale of securities will lower their prices and raises their yields. Price of securities is inversely related to the interest rates (01 yields). Hence, open market operations can also affect interest rates.

III. Effect on Future Expectations:

Open market operations can also affect the economy by changing expectations about the future interest rates. An increase in the purchase of securities by the central bank may be interpreted as an expansionary monetary policy. This will lower interest rates, increase investment, production and employment, and raise consumer spending and prices.

On the other hand, expansionary monetary policy may induce expectations of increased inflation in future which will discourage investment and consumption spending. Thus, nothing specific can be said as to how expectations change as a result of change in the open market operations.

IV. Simultaneous Determination of Interest Rate and Money Supply:

The central bank, through open market operations, cannot simultaneously fix the security price (i.e., interest rate) and the reserves of the commercial banks (i.e., money supply). If the central bank wants to fix the security price, and thus the interest rate, below (or above) the natural rate of interest, i.e., the market determined rate of interest rate, it must be prepared to buy (or sell) an unlimited quantity of securities at the fixed lower (or higher) price, and must accept an increase (or decrease) in the reserves of commercial banks and thus in money supply.

Similarly if the central bank wants to use the open market operations policy to change the money supply in the desired directions, it must surrender its control over the interest rate and must allow it to go where it will go.

V. Open Market Operations Policy during Inflation:

During inflation, with an objective to reduce the volume of credit, the central bank sells securities to the public for which it receives payment by cheque drawn on commercial banks. This reduces the cash reserves of the commercial banks. A fall in the cash reserves of the commercial banks reduces their ability to create credit and results in multiple contractions in the total volume of credit due to the operation of credit multiplier. Thus, investment activity which is based on the bank loans will be curtailed.

VI. Open Market Operations Policy during Depression:

During depression, the central bank attempts to increase the volume of credit by purchasing the securities from the public. The payment made by the central bank to the sellers is through cheques which are deposited with the commercial banks.

This increases the cash reserves and the credit creation capacity of the banking system. Thus, the loans and advances from the commercial banks increase which result in the expansion of investment, employment, output and prices.

VII. Effect on Balance of Payments:

Open market operations policy may be used to influence the balance of payments favourably. For example, the selling of securities by the central bank will contract the volume of credit and generate a deflationary situation, thus reducing the domestic price level.

As a result of this, the country’s exports will increase because of increased foreign demand due to lower prices; and imports will decline because the prices in the foreign countries are relatively higher. Thus, a favourable balance of payments will be achieved.

The policy of open market operations, by directly changing the cash reserves with the commercial banks, attempts to influence the total volume of credit created in the system and ultimately the level of economic activity and the price level of the country.

(i) To influence the cash reserves with the banking system;

(iii) To stabilise the securities market by avoiding undue fluctuations in the prices and yields of Securities;

(iv) To control the extreme business situations of inflation and deflation;

(v) To achieve a favourable balance of payments position; and

(vi) To supplement the bank rate policy and thus to increase its efficiency.

(i) A well-organised and well-developed securities market should exist,

(ii) Sufficient quantity of eligible securities should exist with the central bank,

(iii) Commercial banks should keep reserves just sufficient to satisfy the legal requirements;

(iv) There should not be any interference from extraneous factors. For example, if the central bank purchases securities to inject additional cash into circulation, such money should not go out of the country or should not be hoarded,

(v) Borrowers should respond to the policy of open market operations and the consequent changes in the banking operations.

(vi) There should not be excessive amounts of government debt. In such situation, there might be sharp reactions to the open market operations.

I. Lack of Well-Developed Security Market:

The success of the policy of open market operations requires the existence of a well-organised and well-developed securities market in the country. Lack of such a market renders the policy of open market operations ineffective.

II. Inadequate Stock of Securities:

The policy of open market operations will be successful if there exists a sufficient stock of suitable securities with the central bank. If the stock of securities is limited, the central bank will not be able to sell them at a large scale when it wants to reduce the cash reserves of the commercial banks and to that extent the effectiveness of open market operations is reduced.

III. Excessive Cash Reserves:

The policy of open market operations requires that the commercial bank should keep reserves just sufficient to satisfy the legal requirements. If the banks keep the cash reserves in excess of the fixed ratio, the policy of open market operations will become ineffective because then these banks will purchase the securities being sold by the central bank with their excessive reserves. In this way, the ability of these banks to create credit will not be adversely affected and the purpose of the open market operations will be defeated.

IV. Attitude of the Investors:

The success of the open market operations depends on the assumption that the commercial banks will expand credit whenever they get additional cash and contract credit whenever their cash reserves diminish as a result of central bank’s open market operations. But, in reality, credit expansion and contraction by banks depend more on the mood of the investors.

During boom, when the businessmen are over-optimistic about the future, the banks will not contract their credit even if their cash reserves are reduced by central bank’s open market operations. Similarly, during depression, the purchase of securities from the banks by the central bank may not induce the commercial banks to expand credit despite their cash reserves.

V. Neutralising Extraneous Factors:

The policy of open market operations may become ineffective due to the operation of some extraneous factors in the economy. It is possible that when the central bank buys securities and injects additional cash into circulation, (a) money may go out of the country because of an unfavourable balance of payments; (b) public may board a part of the additional money put into circulation; and (c) the velocity of circulation may itself decrease. All these factors may neutralise the effect of the sale of securities by the central bank.

VI. Direct Access to Central Bank:

The policy of open market operations requires that the commercial banks should have no access to the central banks for financial accommodation. If the commercial banks have a direct access to the central bank, then the reduction in their reserves through open market sale of securities by the central bank may be neutralised by them through borrowing from the central bank.

Similarly, the increases in the cash reserves of the commercial banks as a result of the open market purchase of securities by the central bank may be used by them to repay the outstanding loans from the central bank.

VII. Limitations of Central Bank:

The success of the open market operations is also limited by the willingness of the central bank to incur losses. Open market operations may means losses to the central bank if it is forced to buy securities at a higher price and sell them at a lower price.

VIII. Less Effective during Depression:

The open market operations policy is more successful in controlling an expansion of credit during inflation rather than a contraction of credit during depression. When the central bank buys securities during depression in order to increase the reserves of the commercial banks, the latter generally find it difficult to expand the credit because of the unwillingness of the businessmen and industrialists to borrow on account of low business expectations.

The scope of open market operations is considerably restricted in underdeveloped countries due to the following reasons:

(i) In the underdeveloped countries, the money and capital markets are in their infancy and are not fully developed.

(ii) The central banks in the underdeveloped countries may not possess adequate stock of securities.

(iii) In the underdeveloped countries, many commercial banks have a fluctuating cash reserve ratio and sometimes this ratio is much higher than the minimum legal requirement.

(iv) In the underdeveloped countries, the central banks do not have enough experience in using the technique of open market operations,

(v) In the underdeveloped countries, the open market operations are a very useful method of credit control. Now-a-days, it is increasingly used because of its more direct and immediate impact on the rates of interest and the supply of money.

The open market operations policy is superior to the policy of bank rate in two way:

(i) Open market operations policy is a direct way of controlling credit, whereas the bank rate policy is an indirect way; in the case of the former, the initiative lies in the hands of the monetary authority, while in case of the latter, the initiative lies with the commercial banks.

(ii) Open market Operations have a direct influence on long-term interest rates. The bank rate, on the other hand, directly affects only the short-terms interest rates; long-term interest rates are affected only indirectly.

It is on account of this superiority that the open market operations are now increasingly used to influence the interest rates as well as the prices of the government securities.

The method of variable cash reserve ratio or changing minimum cash reserves to be kept with the central bank by the commercial banks is comparatively new method of credit control used by the central banks. This method was first adopted by the Federal Reserve System of the U.S.A. in 1935 in order to prevent injurious credit expansion or contraction. While the bank rate policy and the open market operations, due to their limitations, are appropriate only to produce marginal changes in the cash reserves of the commercial banks, the method of cash reserve ratio is a more direct and more effective method in dealing with the abnormal situations when, for example, there are excessive reserves with the commercial banks on the basis of which they are creating too much credit, leading to inflationary situation.

Changes in the cash reserve ratio are a powerful method for influencing not only the volume of excess reserves with the commercial banks, but also the credit multiplier of the banking system. The significance of this method lies in the fact that increase (or decrease) in the minimum cash reserve ratio, by reducing (or increasing) the base of the cash reserves of the commercial banks decreases (or increases) their potential credit creation capacity.

Thus, a change in reserve requirements affect the money supply in two ways- (a) it changes the level of excess reserves; and (b) it changes the credit multiplier.

Suppose the commercial banks keep 10% of their cash reserves with central bank. This means Rs.10 of reserves would be required to support Rs.100 of deposit and the credit multiplier is 10 (i.e., 1/10% =10). To check inflation, the central bank raises the cash reserve ratio from 10% to 12%.

As a result of the increase in the cash reserve ratio, the commercial banks will have to maintain a greater cash reserve of Rs.12 instead of Rs.10 for every deposit of Rs. 100 and they will now decrease their lending to get the additional 2% cash. The credit multiplier will fall from 10 to 8.3 (i.e., 1/12% = 8.3).

On the other hand, to check deflation, the central bank may reduce the cash reserve ratio from 10% to 8% and thus make available 2% excess cash reserves to the commercial banks which they utilise to expand credit. The credit multiplier will then rise from 10 to 12.5 (i.e., 1/8% =12.5).

The following are the limitations of the method of variable cash reserve ratio:

(i) This method is not effective when the commercial banks keep very large excessive cash reserves. In such a case ever if cash reserve ratio is raised, ample reserves remain after satisfying the minimum requirements.

(ii) This method is not effective when the commercial banks happen to possess large foreign funds. Thus, even if the central bank reduces the reserves by raising the cash reserve ratio, these banks will continue to create credit on the basis of the foreign funds.

(iii) This method is appropriate only when big changes in the reserves of the commercial banks are required. It is not suitable for marginal adjustments in the reserves of the commercial banks.

(iv) The effectiveness of this method also depends upon the general mood of the business community in the economy. A decrease in the cash reserve ratio may not be able to expand credit during depression because of low future expectations of the investors.

(v) This method is discriminatory in nature. It discriminates in favour of the big commercial banks which, because of their better position, are not much affected by the changes in the cash reserve ratio as compared with small banks.

(vi) Frequent changes in the cash reserve ratio are not desirable. They create conditions of uncertainty for the commercial banks.

(vii) This method affects only the commercial banking system of the country. The non-banking financial institutions are not required to maintain cash reserves with the central bank.

(viii) It is the most direct and immediate method of credit control and therefore has to be used very cautiously by the central bank. A slight carelessness in its use may produce harmful results for the economy.

(ix) This method may have depressing effect on the securities market. The higher cash reserve requirements may lead the commercial banks to sell the securities in hand which, in turn, will reduce their prices in the market.

(i) The narrow market for government securities limits the effectiveness of open market operations. In a narrow market even a small sale of government securities will lead to a significant fall in their prices. The method of variable cash reserve ratio, on the other hand, is more direct and drastic in its effects without any unfavourable repercussion on the prices of government securities.

(ii) In the underdeveloped countries, most of the commercial banks enjoy an excess liquidity. A rise in the bank race or an increase in the sale of government securities may not succeed in mopping up excess liquidity. In such a situation, the use of a more direct method like the variable cash reserve ratio may prove more effective in siphoning off the surplus liquidity.

(iii) To avoid discriminatory effect of the use of variable cash reserve ratio, the central banks in some underdeveloped countries have decided to enforce additional reserve requirements against any future increase in deposits. The additional reserve requirement, which can be raised to 100% will effectively limit the credit creating capacity of the commercial banks which keep excess liquidity.

(iv) In reply to the criticism that the impact of variable cash reserve ratio is too drastic, it may be argued that the drastic effects may be avoided if reserve requirements are changed with due notice and by small degrees.

(v) The use of variable cash reserve ratio as a stabilisation device is more effective than other quantitative credit control methods on the ground that bank lending is directly related to the liquidity ratio of the commercial banks and a change in the variable reserve ratio attempts to affect significantly the liquidity ratios of the banks.

Despite the limitations, the variable cash reserve ratio is a useful method of credit control. It assumes special significance in the underdeveloped countries where the bank rate and the open market operations are not so effective because of a number of limitations. However, this method is to be used with utmost care and discretion.

As De Kock says, “while it is very prompt and effective method of bringing about the desired changes in the available supply of bank cash, it has some technical and psychological limitations which prescribe that it should be used with moderation and discretion and only under obviously abnormal conditions.”

A comparative picture of the distinctive features of the three quantitative credit control methods, i.e., bank rate policy, open market operations and variable cash reserve ratio, is presented below:

All the three methods have two common features:

(i) They are objective and indiscriminatory in nature; they aim at controlling the total volume of credit in the economy without any regard for the uses for which the credit is put.

(ii) They attempt to control credit by influencing the cash reserves of the commercial banks.

Major differences among the three quantitative methods of credit control are given below:

(i) It is an indirect method of influencing the volume of credit in the economy. It first influences the cost and availability of credit to the commercial banks and thereby, influences the willingness of the businessmen to borrow and invest.

(ii) It does not produce immediate effect on the cash reserves of the commercial banks.

(iii) It is suitable when only marginal changes are desired in the cash reserves of the commercial banks.

(iv) It is flexible. It is applicable to a narrower sector of the banking system and therefore can be varied according to the requirement of local situation.

(i) It is a more direct method because it controls the volume of credit by influencing the cash reserves of the commercial banks.

(ii) It affects the cash reserves of the commercial banks through the purchase and sale of securities. So the success of this policy depends on the existence of a well-developed securities market in the economy.

(iv) It is not flexible. It can be applicable to a narrower sector of the banking system and therefore cannot be changed easily and quickly.

(i) It is the most direct method because it controls the volume of credit by directly influencing the cash reserves of the commercial banks.

(ii) It produces immediate effect on the cash reserves of the commercial banks.

(iii) It is suitable when large changes in the cash reserves of the commercial banks are required.

(iv) It is not as flexible as the open market operations policy is. Since it is applicable to the entire banking system, therefore, it cannot be varied in accordance with the requirements of the local situation.

The comparative study of the three quantitative methods of credit control shows that each method has its own merits and demerits. No method, taken alone, can produce effective results. The correct approach is that, instead of selecting this method or that method, all the three methods should be judiciously combined in right proportions to achieve the objectives of credit control effectively.

The quantitative credit control methods- the bank rate, the open market operations and the variable reserve ratio-operate primarily by affecting the cost, volume and availability of bank reserves, and thereby, tend to regulate the total supply of credit. They cannot be used effectively to control the use of credit in particular areas or sectors of the credit market.

The qualitative or selective credit controls on the other hand, are meant to regulate the terms on which credit is granted in specific sectors. They seek to control the demand for credit for different uses by- (a) determining minimum down payments and (b) regulating the period of time over which the loan is to be repaid.

Various selective controls are discussed below:

I. Marginal Requirements:

The method of regulating marginal requirements on security loans was first used in the U.S.A. under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Control over marginal requirements means control over down payments that must be made in buying securities on credit. The marginal requirement is the difference between the market value of the security and its maximum loan value.

If a security has a market value of Rs.100 and if the marginal requirement is 60% the maximum loan that can be advanced for the purchase of security is Rs. 40. Similarly, a marginal requirement of 80% would allow borrowing of only 20% of the price of the security and the marginal requirement of 100% means that the purchasers of securities must pay the whole price in cash. Thus, an increase in the marginal requirements will reduce the amount that can be borrowed for the purchase of a security.

This method has many advantages:

(a) It controls credit in the speculative areas without affecting the availability of credit in the productive sectors,

(b) It controls inflation by curtailing speculative activities on the one hand and by diverting credit to the productive activities on the other,

(c) It reduces fluctuations in the market prices of securities,

(d) It is a simple method of credit control and can be easily administered. However, the effectiveness of this method requires that there are no leakages of credit from productive areas to the unproductive or speculative areas.

II. Regulation of Consumer Credit:

This method was first used in the U.S.A. in 1941 to regulate the terms and conditions under which the credit repayable in installments could be extended to the consumers for purchasing the durable goods. Under the consumer credit system, a certain percentage of the price of the durable goods is paid by the consumer in cash.

The balance is financed through the bank credit which is repayable by the consumer in installments. The central bank can control the consumer credit- (a) by changing the amount that can be borrowed for the purchase of the consumer durables and (b) by changing the maximum period over which the installments can be extended.

This method seeks to check the excessive demand for durable consumer goods and, thereby, to control the prices of these goods. It has proved very useful in controlling inflationary trends in developed countries where the consumer credit system is widespread. In the underdeveloped countries, however, this method has little significance where such a system is yet to develop.

III. Rationing of Credit:

Credit rationing is a selective method of controlling and regulating the purpose for which credit is granted by the commercial banks. Rationing of credit may assume two forms- (a) the central bank may fix its rediscounting facilities for any particular bank; (b) the central bank may fix the minimum ratio regarding the capital of a commercial bank to its total assets. In other words, credit rationing aims at- (a) limiting the maximum loans and advances to the commercial banks, and (b) fixing ceiling for specific categories of loans and advances.

IV. Moral Suasion:

According to Chandler, “In many countries with only a handful of commercial banks, the central bank relies heavily on moral suasion to accomplish its objectives.” Moral suasion means advising, requesting and persuading the commercial banks to cooperate with the central bank in implementing its general monetary policy. Through this method, the central bank merely uses its moral influence to make the commercial bank to follow its policies.

For instance, the central bank may request the commercial banks not to grant loans for speculative purposes. Similarly, the central bank may persuade the commercial banks not to, approach it for financial accommodation. This method is a psychological method and its effectiveness depends upon the immediate and favourable response from the commercial banks.

V. Publicity:

The central banks also use publicity as a method of credit control. Through publicity, the central bank seeks- (a) to influence the credit policies of the commercial banks; (b) to educate people regarding the economic and monetary condition of the country; and (c) to influence the public opinion in favour of its monetary policy.

The central banks regularly publish the statement of their assets and liabilities; reviews of credit and business conditions; reports on their own activities, money market and banking conditions; etc. From the published material the banks and the general public can anticipate the future changes in the policies of the central bank. But, this method is not very useful in the less developed countries where majority of the people are illiterate and do not understand the significance of banking statistics.

VI. Direct Action:

The method of direct action is most extensively used by the central bank to enforce both quantitative as well as qualitative credit controls. This method is not used in isolation; it is often used to supplement other methods of credit control. Direct action refers to the directions issued by the central bank to the commercial banks regarding their lending and investment policies.

Direct action may take different forms:

(a) The central bank may refuse to rediscount the bills of exchange of the commercial banks, whose credit policy is not in line with the general monetary policy of the central bank,

(b) The central bank may charge a penal rate of interest, over and above the bank rate, on the money demanded by the bank beyond the prescribed limit,

(c) The central bank may refuse to grant more credit to the banks whose borrowings are found to be in excess of their capital and reserves.

In practice, direct action as a method of controlling credit has certain limitations:

(a) The method of direct action involves the use of force and creates an atmosphere of fear. In such conditions, the central bank cannot expect whole-hearted and active cooperation from the commercial banks.

(b) It may be difficult for the commercial banks to make clear-cut distinction between essential and non-essential industries, productive and unproductive activities, investment and speculation,

(c) It is difficult for the commercial banks to control the ultimate use of credit by the borrowers,

(d) Direct action, which involves refusal of rediscount facilities to the commercial banks, is in conflict with the function of the central bank as the lender of the last resort according to which the central bank cannot refuse such facilities.

In modem times, the selective credit controls have become very popular, particularly in the developing countries.

They serve to achieve the following objectives:

(i) The selective credit control measures divert credit from nonessential and less urgent uses to essential and more urgent uses.

(ii) The measures influence only the particular areas of the economy (e.g., speculative activities) without affecting the economy as a whole.

(iii) The selective credit controls discourage excessive consumer spending on durable goods financed through the hire-purchase schemes.

(iv) The selective credit controls are particularly useful in the developing countries where quantitative methods are not so much effective because of underdeveloped money market.

(vi) Through selective measures, the central bank can give preferential treatment to the backward and priority sectors, such as agricultural sector, small scale sector, export sector, of the developing economies by providing special credit facilities to these sectors.

(vii) The selective credit controls are helpful in ensuring balanced economic growth. They play an important role in removing various types of imbalances which tend to emerge in an economy during the process of economic development.

(viii) Selective credit controls may also be used in curbing inflationary tendencies in the developing economies. This may be done by encouraging productive investments and restricting unproductive investments.

The selective controls suffer from the following limitations:

(i) The selective credit controls are effective only in influencing the credit policies of the commercial banks and not of the other non-bank financial institutions. These non-bank financial institutions also create a large proportion of total volume of credit and are not under the control of the central bank.

(ii) Through selective credit controls, the monetary authority seeks to divert bank credit from unproductive to productive activities. But, it is not easy for the commercial banks to distinguish between productive and unproductive activities.

(iii) Even if the commercial banks are able to provide loans for productive purposes, it is not possible for them to control the ultimate use of these loans. The borrowers may use these loans for unproductive purposes.

(iv) Under the selective credit control policy, there is no restriction on clean credit. Thus, the selective measures, like higher marginal requirements, may be violated by the borrower who can obtain clean loans from the banks.

(v) The commercial banks, motivated by higher profits, may manipulate their accounts and advance loans for prohibited uses.

(vi) The selective credit controls are not so effective under unit banking system as they are under branch banking system.

(vii)The selective credit controls are also not effective in the indigenous and unorganised banking sector of the developing economies.

Despite these limitations, the selective credit controls are an important tool with the central bank and are extensively used as a method of credit control. However, for effective and successful monetary management, both the quantitative and qualitative credit control methods are to be combined judiciously. The two types of credit control are not competitive; they are supplementary to each other.